Why Trump identifies with war criminals

Trump frames war crime pardons just like he frames impeachment. That's no coincidence.

Army 1st Lt. Clint Lorance was convicted of two counts of second-degree murder and several other charges pertaining "to a pattern of threatening and intimidating actions toward Afghans" as a platoon leader in Afghanistan. The ruling relied on the testimony of nearly a dozen of the men who served under him, accounts describing an "ignorant, overzealous, and out of control" officer who "hated the Afghan people" and spent his days "tormenting the locals and issuing death threats." Lorance's conviction included at least one crime every single day at the station in question.

This month, President Trump pardoned Lorance and another U.S. soldier convicted of war crimes while restoring the rank of a third subject to similar accusations. "Just this week I stuck up for three great warriors against the deep state," Trump boasted at his Florida rally Tuesday night. His rationale for issuing the pardons was threefold: First, because he likes the military so much ("I will always stick up for our great fighters"); second, because he wanted to reunite the families separated by these convictions ("He hugged his parents; it was a beautiful, beautiful thing"); and third, because he wants U.S. soldiers to feel free to do whatever it takes to keep America safe ("People have to be able to fight").

This is a load of tripe with a dash of trolling. The bit about the beauty of reuniting families seems calculated to infuriate opponents of this administration's zero-tolerance policy of separating migrant families at the border. That's the trolling. As for the rest of it, what Trump actually likes is war crimes, and, I suspect, he sees parallels here to himself. He wants his own history of fighting dirty to be likewise excused.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The president's affection for violence beyond the laws and norms of modern warfare is well-established. He expresses total confidence in the efficacy of torture, despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary, and insists it should be employed even if it doesn't work ("They deserve it anyway for what they do to us"). In a 2016 op-ed, for example, Trump argued it is only political correctness that prevents the United States from drowning and beheading our enemies in the style of the Islamic State. He has waxed rhapsodic about the prospect of killing the families of terrorists — which is to say, murdering children because of the misfortune of their birth and slaughtering women who very possibly had no choice in their marriage. He has no interest in confining the U.S. military to the rule of law, whether domestic or international, instead envisioning himself as the war crime commander-in-chief: "If I say do it, they're going to do it."

Thus the twisted mercy Trump offers in pardoning war crimes is not a boon to the U.S. military. It is a degradation, a blood offering to Mars.

This enthusiasm for cruelty might be sufficient to get Trump to issue pardons for war crimes. He has made clear he doesn't care whether these soldiers are innocent of what they are accused of doing and in fact believes they were right to do it if indeed they are guilty. But I think there's another factor at work: Trump in a sense identifies with the men he has pardoned. He is giving them the indemnity he hopes for himself.

"You know what I'm talking about," Trump said in Florida. "I had so many people say, 'Sir, I don't think you should do that.' People have to be able to fight. These are great warriors. They can't think, 'Gee whiz, if I make a mistake, do I go [to jail] for it?'" he continued. "People can sit there in air-conditioned offices and complain, but you know what? That doesn't matter to me whatsoever. [The soldiers are] out in that field, and they're doing a job for us like nobody else anywhere in the world can do."

Add in the "deep state" line from earlier in the speech and here's what you get: The Washington establishment is conspiring to stop our hero from doing what needs to be done — what he alone can do — for America. These prissy bureaucrats are obsessing over rules and niceties, bitching about the champion's commitment to fight for our country however he can.

Sounds familiar, no? It's Trump's framing of his war crimes pardons, but it's also his framing of the impeachment inquiry against him, in which — as he put it in Florida — "the failed Washington establishment is trying to stop me because I'm fighting for you and because we're winning."

Lorance and the other alleged and convicted war criminals Trump has pardoned would have attracted the president regardless. His rhetoric about torture and violence made that evident long before he was subject to accusations of corruption. But now that those accusations have been leveled, there is an added appeal. Trump has espied an opportunity to protect in parallel his own foul play. He has found a way to give the pardon he wants.

Create an account with the same email registered to your subscription to unlock access.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Bonnie Kristian was a deputy editor and acting editor-in-chief of TheWeek.com. She is a columnist at Christianity Today and author of Untrustworthy: The Knowledge Crisis Breaking Our Brains, Polluting Our Politics, and Corrupting Christian Community (forthcoming 2022) and A Flexible Faith: Rethinking What It Means to Follow Jesus Today (2018). Her writing has also appeared at Time Magazine, CNN, USA Today, Newsweek, the Los Angeles Times, and The American Conservative, among other outlets.

-

'Horror stories of women having to carry nonviable fetuses'

'Horror stories of women having to carry nonviable fetuses'Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

By Harold Maass, The Week US Published

-

Haiti interim council, prime minister sworn in

Haiti interim council, prime minister sworn inSpeed Read Prime Minister Ariel Henry resigns amid surging gang violence

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

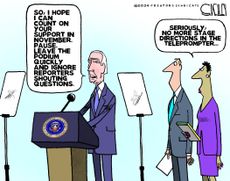

Today's political cartoons - April 26, 2024

Today's political cartoons - April 26, 2024Cartoons Friday's cartoons - teleprompter troubles, presidential immunity, and more

By The Week US Published

-

Arizona court reinstates 1864 abortion ban

Arizona court reinstates 1864 abortion banSpeed Read The law makes all abortions illegal in the state except to save the mother's life

By Rafi Schwartz, The Week US Published

-

Trump, billions richer, is selling Bibles

Trump, billions richer, is selling BiblesSpeed Read The former president is hawking a $60 "God Bless the USA Bible"

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

The debate about Biden's age and mental fitness

The debate about Biden's age and mental fitnessIn Depth Some critics argue Biden is too old to run again. Does the argument have merit?

By Grayson Quay Published

-

How would a second Trump presidency affect Britain?

How would a second Trump presidency affect Britain?Today's Big Question Re-election of Republican frontrunner could threaten UK security, warns former head of secret service

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

'Rwanda plan is less a deterrent and more a bluff'

'Rwanda plan is less a deterrent and more a bluff'Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

By The Week UK Published

-

Henry Kissinger dies aged 100: a complicated legacy?

Henry Kissinger dies aged 100: a complicated legacy?Talking Point Top US diplomat and Nobel Peace Prize winner remembered as both foreign policy genius and war criminal

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Last updated

-

Trump’s rhetoric: a shift to 'straight-up Nazi talk'

Trump’s rhetoric: a shift to 'straight-up Nazi talk'Why everyone's talking about Would-be president's sinister language is backed by an incendiary policy agenda, say commentators

By The Week UK Published

-

More covfefe: is the world ready for a second Donald Trump presidency?

More covfefe: is the world ready for a second Donald Trump presidency?Today's Big Question Republican's re-election would be a 'nightmare' scenario for Europe, Ukraine and the West

By Sorcha Bradley, The Week UK Published