Turkey's moment of truth

Turkey is in the midst of a frightening financial crisis. What can be done to save its economy?

Turkey is in crisis. And things will probably get considerably worse before they get better.

Over the last several days, the Turkish lira has plunged against the U.S. dollar, falling as much as 20 percent before recovering ever so slightly. But it remains near record lows, down 70 percent over the year. Turkey is grappling with interest rates of almost 18 percent and inflation of 16 percent. Analysts fear the crisis will soon spread internationally.

What's causing Turkey's downward spiral? Basically, Turkey committed one of the cardinal sins of macroeconomic management: It borrowed heavily in a currency it doesn't control. More specifically, Turkish corporations borrowed heavily in a currency the Turkish government doesn't control.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From 2005 to 2017, the debt load of Turkish corporations leaped from 20 percent to nearly 70 percent of the country's GDP. That borrowing drove years of robust economic expansion, making Turkey the fastest growing member of the G20 in 2017. But over half of that borrowing was done in foreign currencies — mostly U.S. dollars — instead of lira. And much of that debt is held on the balance sheets of domestic Turkish banks, who were happy to facilitate the borrowing spree.

This was all well and good until mounting trade tensions with America, combined with pre-existing nervousness about inflation, interest rates, and the rest, finally inspired international investors to all flee the lira at once.

The problem with borrowing in dollars and euros is that the Turkish state retains little control. Of course, Turkey has its own central bank and controls the supply of its own currency. If the domestic economy overextends itself by borrowing in liras, the government can always print more and bring down interest rates. Doing so would risk overheating the economy and driving up inflation. But so long as a country's economy does the vast majority of its borrowing in the country's own currency, the government has broad leeway to address problems and correct imbalances.

But the Turkish government can't really help when the debts are owed in currencies controlled by other governments. Indeed, if the Turkish state were to undertake such a money-printing effort now, it would drive the lira even lower in value. The more the lira falls, the harder and harder it becomes for Turkish businesses and banks to pay off their foreign-denominated debts. That's precisely the reason for the current panic: If the lira falls enough, a massive wave of major Turkish companies and financial institutions could go belly up. That could drag down banks in other countries and spark a much wider international crisis.

Turkey could get the money to pay off its $343 billion in foreign debts by running big trade surpluses, and exporting far more than it imports. But it wouldn't be easy to get there, since Turkey is already dealing with a really deep trade deficit. (In a bitter irony, the best way to get from a trade deficit to surplus is to, well, lower the value of your currency.) That President Trump just doubled the tariffs on Turkish steel and aluminum certainly won't make it any easier for the country to export more.

Now, the mechanisms of a market correction are already in play. Should the lira continue to fall, Turkey's trade balance will improve. A string of bankruptcies across the country's industrial, real estate, and financial sectors would also drive down incomes, lowering the value of the lira further — and again, drive Turkey's trade balance into the black. The bankruptcies themselves would relieve much of the foreign debt burden. And the shift in the trade balance would enable the country to pay off much of the rest.

In short, the "natural market correction" scenario is that Turkey goes through a massive recession. That corrects its economy's imbalances and allows it to eventually rebuild.

There's just the minor problem that recessions destroy millions of livelihoods and cause massive amounts of human suffering.

Furthermore, Turkey is already sinking into reactionary authoritarianism under President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. A major economic collapse could make things worse.

Turkey does have one ace in the hole it could play ... but it's not a cure-all.

The Turkish government has actually run low deficits — generally 2 percent of GDP or less — since the early 2000s. This is not something to celebrate: Had Turkey's government run much greater economic stimulus, that would've driven Turkey's economic boom rather than foreign-denominated debt. And the country would now be in a much better spot.

But the government can still run big stimulus now, and counteract the upheaval of the lira's plunge. As its banks and companies collapse, Turkey could step in with much more aggressive industrial policy to create jobs and investment through lira-printing. It could also finance a vast expansion of welfare state policies to preserve the incomes of Turkish families and prevent mass destitution. Granted, this would also require extensive capital controls to prevent the government's new investments from also fleeing the country. And that would probably infuriate the wealthy both in Turkey and abroad. But basically, Turkey could allow the "market correction," but use it as an opportunity to shift the economy onto a different investment and growth model.

Now, observers might argue that the Turkish government doesn't have the room to do this: Inflation and interest rates are already quite high, so the economy is already overheating. But Turkey's unemployment rate is around 10 percent, and its labor force participation is lackluster. This is not an economy on the brink of overcapacity.

Rather, it looks like Turkish inflation is, paradoxically enough, driven by the fall in the lira: With so much of the Turkish economy run on U.S. dollars, the drop of the domestic currency is driving up dollar-denominated prices. The interest rates are simply a (not very well focused effort) to bring those prices back down. Cleansing the Turkish economy of its reliance on U.S. dollars should end that feedback loop, allowing prices and interest rates to fall.

Of course, the bigger political question is whether a government run by an authoritarian demagogue like Erdoğan has the judgment, temperament, or policy acumen to actually pull this off. I wouldn't hold my breath. And even if they can save Turkey's economy and workers, saving its financial sector — and, by extension, international financial markets — is a whole other issue.

This is still probably the least bad option Turkey has — which is perhaps all you need to know about the severity of the crisis Turkey is in.

Create an account with the same email registered to your subscription to unlock access.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

'Elevating Earth Day into a national holiday is not radical — it's practical'

'Elevating Earth Day into a national holiday is not radical — it's practical'Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

By Harold Maass, The Week US Published

-

UAW scores historic win in South at VW plant

UAW scores historic win in South at VW plantSpeed Read Volkswagen workers in Tennessee have voted to join the United Auto Workers union

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

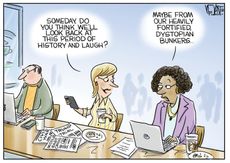

Today's political cartoons - April 22, 2024

Today's political cartoons - April 22, 2024Cartoons Monday's cartoons - dystopian laughs, WNBA salaries, and more

By The Week US Published

-

Geopolitics and the economy in 2024

Geopolitics and the economy in 2024Talking Point The West is banking on a year of falling inflation. Don't rule out a shock

By The Week UK Published

-

US-led price cap on Russian oil 'almost completely circumvented'

US-led price cap on Russian oil 'almost completely circumvented'Speed Read 'Almost none' of seaborne crude oil from Moscow stayed below $60 per barrel limit imposed by G7 and EU last year

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

Mexico's Sinaloa cartel bans fentanyl, reportedly under pain of death

Mexico's Sinaloa cartel bans fentanyl, reportedly under pain of deathSpeed Read The top exporter of fentanyl to the U.S. is apparently looking to diversify as law enforcement turns up the heat

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

The threat posed by bonds to the global financial system

The threat posed by bonds to the global financial systemUnder The Radar The worst bear market in a century is unleashing huge strain on parts of the financial system

By The Week Staff Published

-

China: a superpower’s slump

China: a superpower’s slumpThe Explainer After 40 years of explosive growth, China’s economy is now in deep distress — with no turnaround in sight

By The Week Staff Published

-

Are Western sanctions working on Russia’s growing economy?

Are Western sanctions working on Russia’s growing economy?Today's Big Question IMF forecasts Russian growth but one expert says the West must be patient in bid to deter Putin

By Arion McNicoll Published

-

South Africa’s energy crisis explained

South Africa’s energy crisis explainedfeature Electricity blackouts lead to rising crime and economic hardship and add to pressure on ANC

By The Week Staff Published

-

India’s geopolitical aspirations in 2023

India’s geopolitical aspirations in 2023feature The emerging Asian superpower is showing ‘growing confidence’ on the world stage

By Chas Newkey-Burden Published